THE WAR ON TERROR Part 3

EDITOR'S NOTE: THIS IS PART THREE OF A FOUR-PART SERIES THAT WILL RUN IN FRIDAY EDITIONS OF THE BLADE-EMPIRE NEWSPAPER.

As a Concordia youth who loved hunting in the outdoors, Heath Trost didn't know he had already begun training for a career as a soldier in America's elite Special Forces. He joined the Army at the age of 18 just hoping to earn some money for college. Instead, he was selected to become an Army Ranger, and then a member of America's foremost military assault unit: 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-DELTA.

For the better part of 10 years Trost was deployed in active combat zones, putting his life on the line to hunt down terrorists who were determined to inflict death and suffering on the United States of America.

IRAQ 2003-2005: HUNTING THE DECK OF CARDS

In 2003 Trost was a HMMV (Humvee) machine gunner in a DELTA assault force in Iraq. Though his unit was based in Baghdad - a city of 8 million and the former epicenter of an enemy regime - on any given day DELTA pushed east, west, north, and south beyond the city limits.

"We had specific types of responsibilities," he said, "and those responsibilities could be anywhere."

The enemy insurgency hadn't coalesced into a cohesive resistance unit yet. The brutal regime of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussien had only recently been toppled, and American military forces were out searching for Hussein and other former Iraqi leaders who were on the run.

"We were hunting the deck of cards," Trost said.

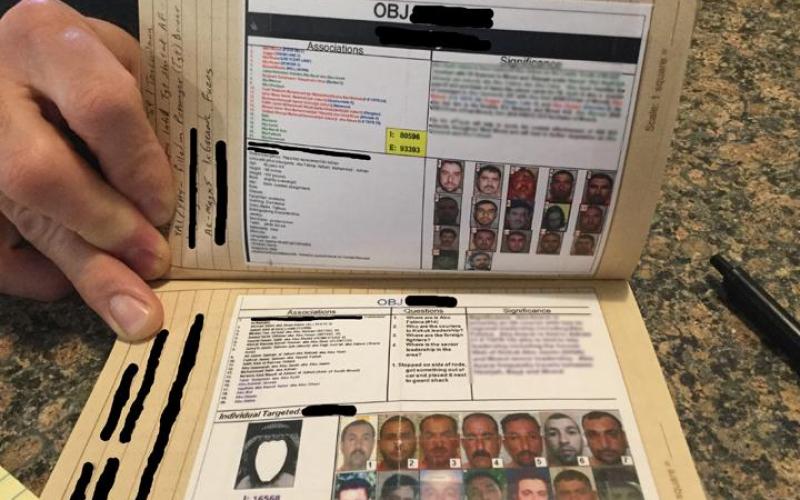

During the 2003 invasion of Iraq the U.S. military produced a set of playing cards to help troops identify the most-wanted members of Hussein's government, mostly high-ranking members of the Iraqi Regional Branch of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party, and members of the Revolutionary Command Council.

Saddam Hussein was the Ace of Spades.

"Every day we would receive intel, and every day we were on the streets or out in the countryside looking for bad guys," Trost said.

As the months passed the al-Qaeda insurgency began to gain strength in the war-torn country. One terrorist quickly rose to the top of the Most Wanted list because of his ruthless tactics and ability to mount widespread terror campaigns against American military forces.

Delta Force called him AMZ. His name was Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a Jordanian-born jihadist who became infamous for hundreds of bombings, beheadings, and civilian attacks that nearly turned an Islamic insurgency movement into all-out civil war in Iraq.

"We processed several of their kill houses," Trost recalled. "We'd find Iraqi civilians who had been tortured and beheaded because they were suspected of collaborating with American forces."

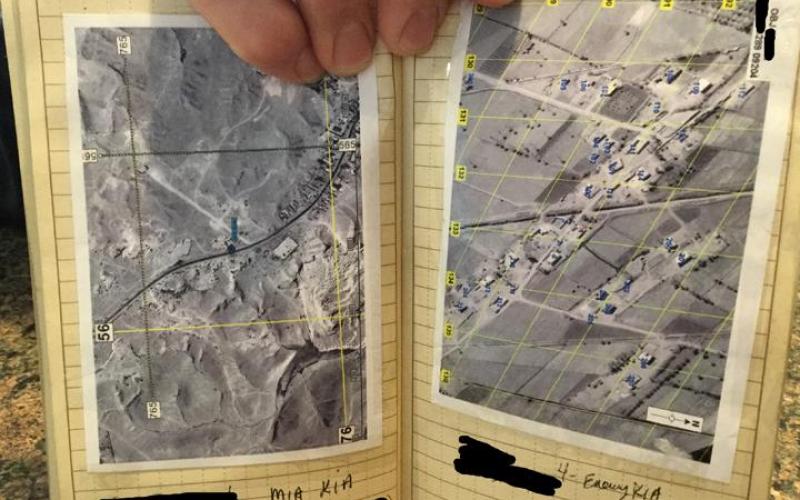

On a daily basis, Trost's DELTA unit would be given aerial reconnaissance photos of enemy target sites: buildings in crowded cities; isolated homes in the rural countryside; palm tree groves set amid the arid desert terrain; and mountainous regions inundated with caves. All of them were potential ambush sites for American soldiers.

Sometimes Trost's unit was called in for rescue operations. Trost vividly recalls one mission to try and rescue a Marine who was missing after his outpost was overrun by al-Qaeda insurgents. An aerial drone had located the terrorists near a cave complex. As Trost's DELTA unit deployed for a rescue mission, Trost watched real-time video from the orbiting drone of the Marine being dragged from the trunk of a car. He had been tortured to death. The rescue mission became a body retrieval.

"Things like that remind you why we do what we do," Trost said.

Al-Qaeda had their own cameras at the site and were attempting to pose the dead Marine for propaganda photos and videos when DELTA arrived.

"We didn't take any prisoners that day," Trost said matter-of-factly.

Over the next several years each combat deployment became different for Trost. As the al-Qaeda insurgency in Iraq gained strength it adapted to the tactics of the U.S. military and devised effective countermeasures.

"The ROE (Rules Of Engagement) were always changing," Trost said. "Some of those people are extremely smart and extremely talented at devising terror tactics. They learned from their mistakes. They evolved and became even more deadly."

When Trost was first deployed on a combat tour, his DELTA unit rode in HMMVs to "hard hit" an insurgent stronghold, using speed and surprise in direct assaults against houses in the cities and in rural areas.

"We knocked on their door," Trost said, which is DELTA-speak for blowing apart the door and storming inside the house.

The enemy adapted. They began inlaying machine gun bunkers two doors deep into their strongholds.

"They took our speed, surprise, and violence of action and turned it on us by shooting directly at our entry points," Trost said.

In the 16 years of America's involvement in the Iraq war, 2005 was the deadliest year for its Special Forces units.

"We lost too many of my brothers that year," Trost said.

To counteract the terrorists' own countermeasures, the American military reverted to heavy armor assault forces that would hit an enemy target like a sledgehammer.

"Now we did 'Call Outs'," Trost said. "An interpreter travelled with our units. The mechanized armor would surround the target area and the interpreter would try to talk the enemy into surrendering. Again, we were letting them 'vote' on their own fate. Surrender or die."

Few jihadists surrendered. A K-9 would be sent into the building to see if there were women and children inside. If so, the assault team would lay siege to the building. If there were only terrorists inside, an air strike was called in and the building was obliterated by post-assault fire.

Once again, the terrorists adapted. The American military predominately used vehicles to traverse the country on raids. Terrorists developed IED's (Improvised Explosive Devices) and planted them in roads or in cars parked in the streets around their strongholds. With lookouts posted everywhere to give advance warning, day and night, the terrorists would detonate the IED's as soon as a military vehicle appeared. IED's evolved into VBIED's (Vehicle-Born Improvised Explosive Devices), car bombs that would intentionally be driven into an approaching military force or military checkpoint and detonated, causing massive casualties.

Special Forces countered this tactic by going airborne, using helicopters to intercept VBIED's from the air. Trost was a designated sniper stationed in the open door of a DELTA helicopter.

"We'd get intel from OGA (Other Government Agencies) that a VBIED was on the move," Trost said. "We'd intercept it from the air and direct it to stop by shooting in front of the vehicle."

If the vehicle kept moving, machine gunners used a procession of shots fired into the engine block and wheel drums.

"It's not like in the movies," Trost said. "Shooting out the tires hardly every works."

If the vehicle continued to try and evade the DELTA team, sniper Trost was given the order to eliminate the driver.

"When I first started combat deployments we were in HMMVs driving down roads," Trost said. "Then we moved up to a heavy armor assault force; and then to helicopters and we never touched ground unless we had a hard target to kill/capture."

Day-after-day, deployment after deployment, Trost was hunting down terrorists who were willing to sacrifice their own lives to inflict death and suffering on others. War is brutal, frightening, merciless. On a daily basis fanatical men - and women - armed with a multitude of weapons and bombs were trying to kill American soldiers. Trost had so many close calls with death it became a possibility he just accepted.

"Sometimes, really, life-and-death was just a matter of inches," he said.

On October 24, 2005, Heath Trost nearly ran out of inches.

Early that morning a sortie of Black Hawk helicopters landed in a remote field in the Al Asad province of western Iraq. Trost was the #4 man on three DELTA assault teams that began a seven kilometer infiltration march to a village near the Syrian border. They were hunting a terrorist who built explosive vests for suicide bombers. The teams reached the target house set amid a grove of palm trees and quickly prepared for an assault entry. Trost blew apart the reinforced front door and his team stormed inside. They kicked in another closed door and found the terrorist standing in a bedroom. Wires extended from the right sleeve of the terrorist's shirt to his hand.

"It all seemed to happen in slow motion," Trost recalls. "The #1 man on my team fired; the terrorist instinctively turned away from the bullets just as he detonated his suicide vest."

When the terrorist turned away the brunt of the explosive blast was directed at the bedroom wall, away from the DELTA assault team. But blasting away the wall exposed four other terrorists wearing suicide vests who were hiding in the room. Their vests also detonated. The concussive blast of the combined explosions was so powerful it lifted Trost's body into the air and flung him back through the doorway, and also destroyed the support beams of the reinforced house, bringing the roof down on top of everyone.

Trost regained consciousness, his vision blurred and his ears ringing like a fire alarm. He dug himself out of the smoking rubble and began searching for his team members. They were also buried in the rubble but miraculously still alive.

All five terrorists had been killed by the bomb blasts.

A matter of inches.

Trost led the call out; the DELTA teams regrouped and raided the house next door, where they found two more suicide bombers.

Eight hours after the mission began, Trost and his assault unit walked four kilometers to helicopters waiting to extract them to safety. Trost had shards of glass and debris imbedded in his body and his face and hair were burned by the bomb blasts.

"We should've all been sent to our maker that night," Trost said. "We all should have died."

Most people who survive a near-death experience are affected by it, at some level, for a long time afterward. Whether its loss of sleep or anxiety or panic attacks or nightmares or deeper psychological issues, the human psyche reacts differently to the narrow avoidance of death.

Trost doesn't give that night much thought anymore.

"It is what is," he said. "We got lucky; we lived. But there were so many instances in my military career when I was seconds away or one wrong turn away from being killed. You think about it, but you don't dwell on it. That's part of the training we go through. We train to eliminate fear. I was trained to do this job for my country."

Trost was awarded the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star with Valor for his actions that day in the Al Asad Province.

The American military awards the Bronze Star to "soldiers of the United States Armed Forces for heroic achievement, heroic service, meritorious achievement, or meritorious service in a combat zone."

During his 27 years of military service to America, and his 10 combat tour deployments, Heath Trost would be awarded three more Bronze Stars for heroism and bravery.

NEXT FRIDAY: HUNTING HIGH-VALUE TARGETS...

THEN THE HUNTER STEPS DOWN